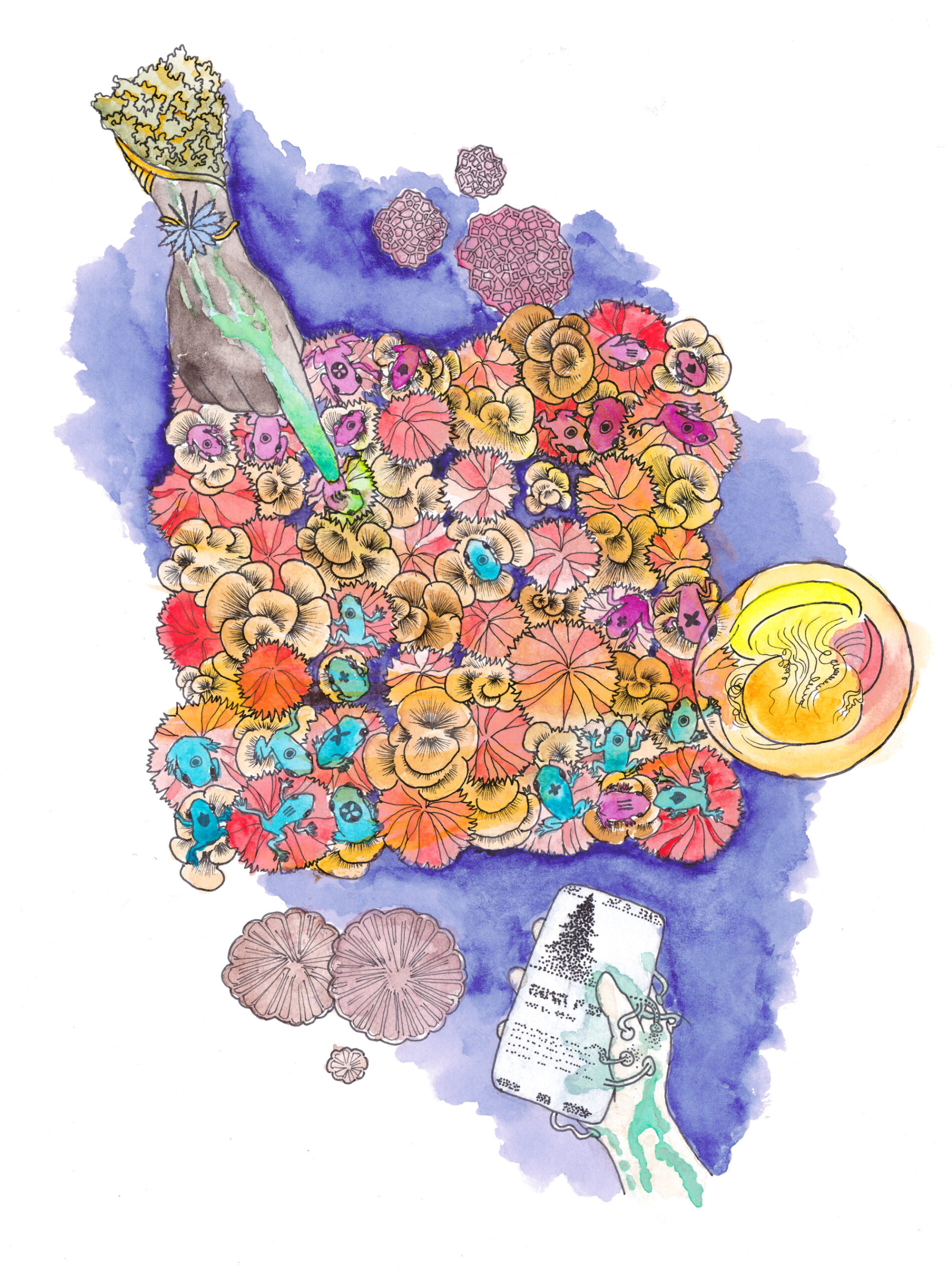

“Everything we touched was alive. Each morning I woke up in a bed made of mushroom, covered in sheets of fresh spider silk. The limbs of our home opened with sunrise. I didn’t need an alarm clock; the microbes in my gut secreted neurotransmitters to wake me. Nobody really used caffeine anymore. When I went to work, I boarded a train that zipped up the single-stranded railway in one direction, and unzipped along the double-tracked route on the way back. Instead of a cell phone, I gazed at a beautiful organic ecosystem with fluorescent proteins arranged to display the news. My teeth stayed clean naturally, a self-balancing ecosystem consuming the excess sugar from my diet. Everything, absolutely everything, was alive.”

He looked across the table at his son, who was listening intently, eyes peeled in delight, then regarded his sister, whose eyes were damn near rolling back in her head.

“I’m impressed you can still say all that with a straight face,” she grumbled. “Really wasn’t all that great, you know. Try getting a good drink back then! I ordered wine at your wedding, and all I got was sweet purple sap! The bartender handed it to me so smugly and said there was no need for brute chemicals anymore. ‘Maybe not for you, there isn’t.’ I said.”

“Everything was alive?” the son said, still staring at his father. “Literally everything?”

“Yes, everything.”

“Cups?”

“Disintegrated like ants when you dropped one on the ground.”

“Roads?”

“Self-healing fungal mats.”

“Smelled like an old brewery,” she said. “Everything smelled like yeast. Warm mold and yeast.”

“Clothes?”

“So many beautiful clothes. Mosses and sheer threads growing down from fungal collars. Shoes like warped bonsai. Coils of vines all laced with flowers and petals. Living fur jackets.”

“Windows? Cities? Lights?”

“Diatomic glass, orchards as far as you could see, bioluminescence on command!”

“Everything looked kinda shapeless, run down,” she muttered.

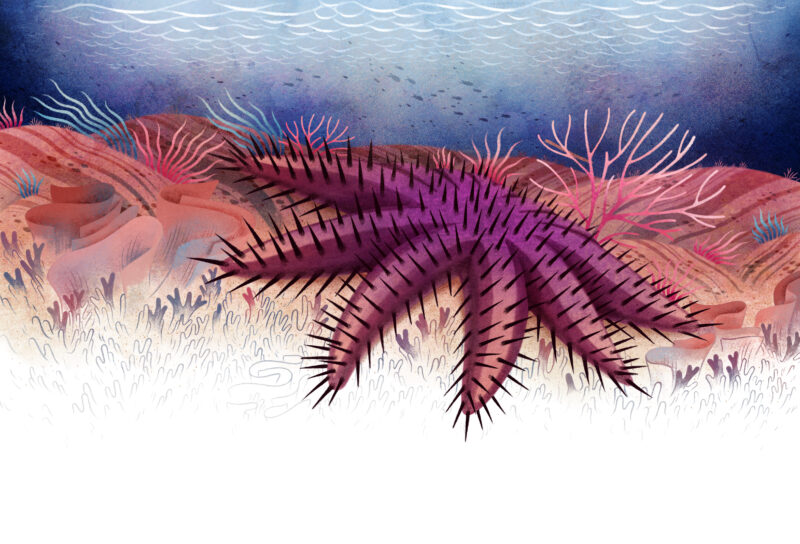

“Your aunt’s mad because she didn’t contribute her part. She also never saw the coral communities down South.”

His son giggled, he laughed along, and his sister stood up stormily. “Your little eco-dictatorship did us all a lot of good, didn’t it?”

Father and son both watched her mirthfully as she walked out of the room.

“Tell me about the MetaBiome again.”

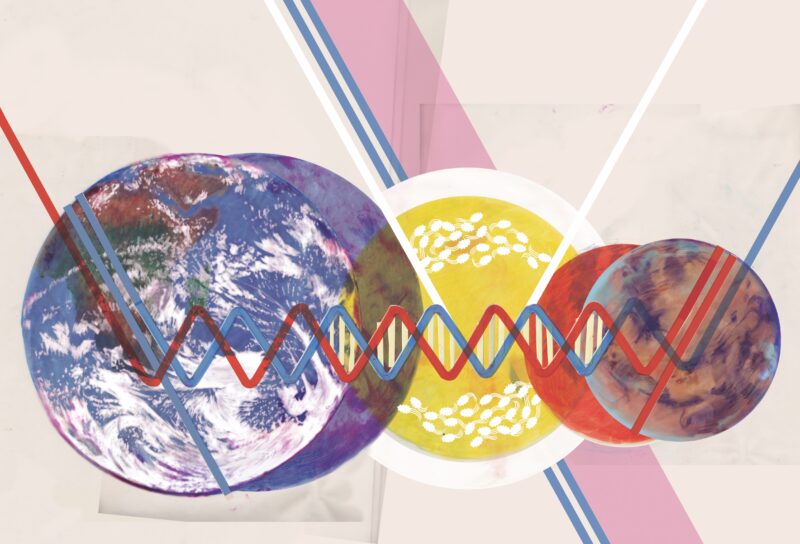

“It connected everything: A vast interweaving network of underground bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms we designed specifically to support and renew the world.”

They beamed at each other. How often had they had this conversation! Seeing his father so happy never got old.

He was only ten, but already he could tell that every time his father told the old stories, the gleam in his old eyes had died a tiny bit, the sentences lost a bit of their conviction. Certain details started to lose sharpness, particularly when he talked about the replacement for money they had invented at the time. “They developed this…set of organisms. Called them MetaBiotics. The name wasn’t great, but take a look at old cryptocurrency names….They mediated all our interactions. We incubated MetaBiotics inside of ourselves, and they would signal our intentions out into the living world….It was all so seamless and harmonious.”

He had learned to stop asking his father how it had all collapsed. His father didn’t like telling that part of the story. He would grow bitter and plaintive, wallowing in his room for hours afterwards. When that part came up, his father was the one pouting (“corporate coup!”), and his aunt became the proud custodian of recent history.

“MetaBiotics were viruses, okay?” his aunt would say. “They did what viruses do. Used us to multiply. We thought they were serving us, until it turned out that we were serving them. Your dad and his buddies were their useful idiots. Started saying stuff like “MetaBiotics make the man,” thinking they were better because they had more. People got greedy. Harmonious, my ass!”

“I’ll be the first to admit that not everything worked perfectly, it never does…”

“Imperfect would be one thing! The MetaBiotics mutated and became pathogenic. Whole city blocks were rotting. Everything smelled horrible. Everyone was infected. We had to do something!”

“Everyone was happy,” his dad said, gazing at his old hands. “Everyone worked. My teeth cleaned themselves.”

“Now you have to brush them, bless your heart, and Nature is still doing her own thing.” She nodded at both of them primly, rising to go to work at the fermentation plant. Dad quietly admonished her and shuffled off to boil himself some more green sap.

Outside, the Pragmatists and their contractors continued to reinforce moss roads with concrete, plant pipes in the ground, and erect cell phone towers into the sky. Only the outlines of the MetaBiome remained, houses like huge flowers, beds like mushrooms, because people had taken a liking to its natural curves and colors.